Don't call him a Chinaman

- Roy McDonald

- Nov 16, 2024

- 5 min read

In August 1932, Prescot Cables staged a series of trial games prior to the start of the season. A young wing-half caught the eye with his hard tackling and accurate passing and was signed up by the Amber and Blacks.

“Frankie” Soo immediately made himself a favourite with the Hope Street faithful, and turned in regular sparkling performances before being snapped up by Stoke City in January 1933. It is testament to the impression he made in Prescot in the few months that he was there, that he is still talked of today.

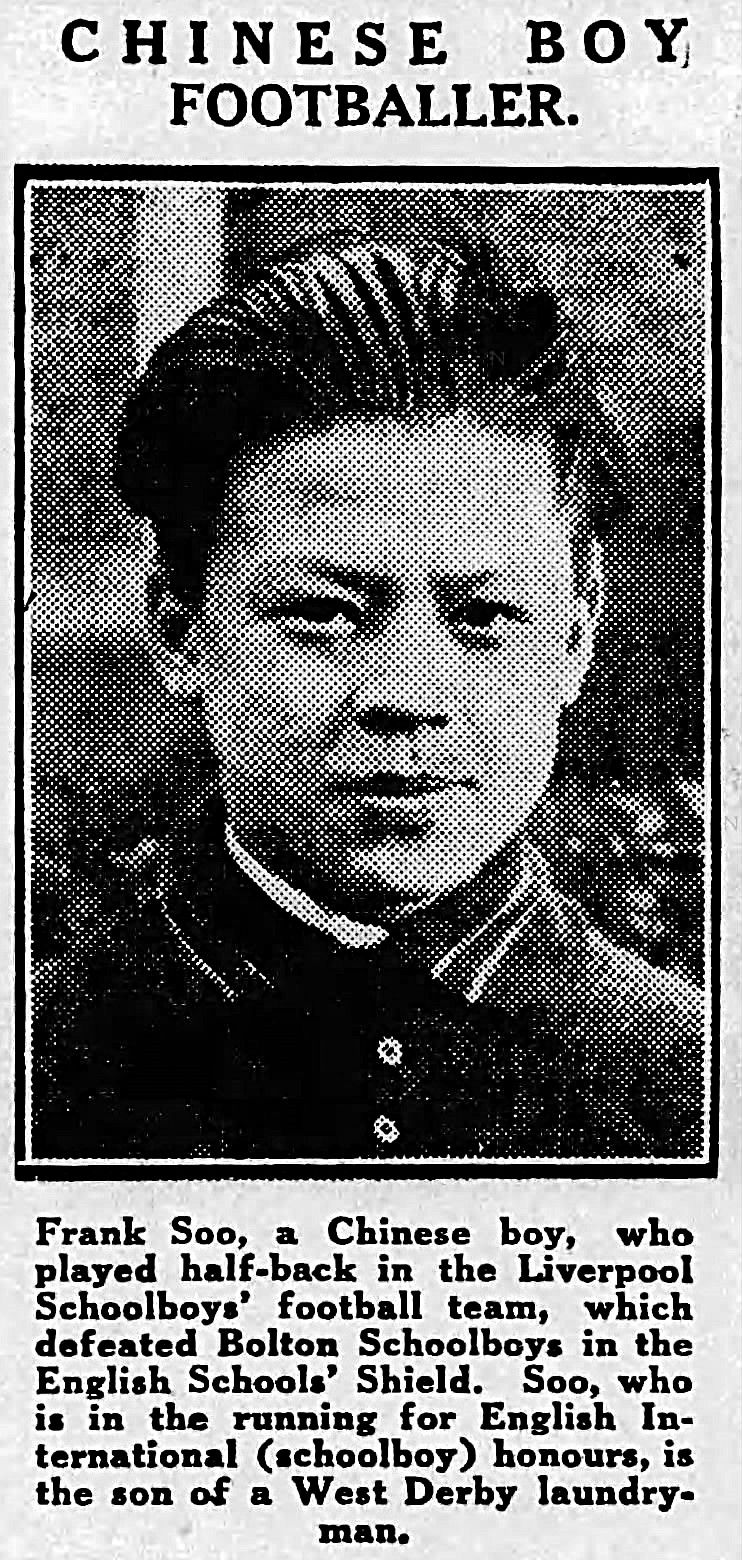

Frank “Frankie” Soo was born in Buxton in March 1914 to parents, Quan and Beatrice Soo, who ran a laundry. Early in Frank’s life the family moved from Derbyshire to a laundry in Town Row in the West Derby area of Liverpool. Frank was an outstanding junior footballer, playing for West Derby Boys Club, Woodville and Liverpool Schoolboys. In those days the Liverpool Schoolboys matches could attract up to 15,000 spectators! In January 1929, the Liverpool Echo noted that he “still seems unspoiled by the hero worship of which he is the recipient”. Despite his “star-status” in the schoolboy side, he was never selected for the Lancashire County side or the England schoolboys squad.

Prescot Cables was a rich hunting ground for the Football League clubs and a host of club scouts would be present at each game, running their eye over potential recruits. After only 4 months at Hope Street, the Stoke City manager, Tom Mather, audaciously signed him from under the noses of a host of First Division clubs for “a fee of between £300 and £400”, in January 1933 (Soo, himself, later said that his transfer was “around £350”). On his signing, Soo said, “I have been well advised apparently, and Stoke will be very kind to me, just as Prescot have been, and I hope to make good.”

Mather later recounted how the signing had come about. He had received a letter from a Stoke man living in Lancashire. The correspondent declared that he had never before written to a football manger but, having seen Soo play for Prescot Cables, he felt it was his bounden duty to communicate with the manger of his home town team. Mather made it his business to watch Soo in action as soon as possible, and saw a strong, clever player with a great idea as to how and when to part with the ball. He immediately had the impression that Soo could develop into a forward.

The signing caused quite a stir but, quite rightly, Mather advised reporters writing about the signing that it was quite wrong to call Soo a Chinaman. Of course, the newspapers paid little heed to this and made great play of his origins. In interviews Frank, himself, was keen to stress that he was not a Chinese player and had never been outside England. In an interview in the 1970’s it is clear that he considered himself a Liverpudlian, saying, “It was unforgivable [for me] not to try, especially if you came from Liverpool, as I did”. He was also quick to play down any racial tensions that he faced, saying, “My answer to the players who used to swear at me and call me a ‘Chinese basket’ was to play my best”.

Originally a half-back at Cables, Tom Mather converted him to an inside-forward. His skilful performances, but more likely, his novelty, meant that crowds of more than 8,000 were attracted to Stoke’s reserve team games. Soo made his first team debut in November 1933 at Middlesbrough, although his side lost the game 6 - 1. Remarkably, the Evening Chronicle in Newcastle upon Tyne wrote that “Teeside soccer fans were wondering if Frank Soo would turn out for Stoke… in his bare feet. For most Orientals prefer to play football minus footwear. For the good reason that their own slippers have no more kick in them than a stubby toe!”

Soo eventually went on to make 185 “official” appearances for the Potters, scoring 10 goals, including a spell captaining the side. He made many more appearance for the Potters in wartime games.

Soo was aged 25 at the outbreak of war in 1939, which interupted his career, just as it was peaking. He took a job in the Michelin tyre factory in Stoke, but in 1941, he joined the RAF as a training instructor, and guested for a number of teams across the country including Chelsea, Everton, Newcastle United, Millwall and Brentford. He was selected to represent England in nine Wartime and Victory internationals – although these have never been recognised as full caps. He was, thus, the first man from a Chinese or East Asian background to play for England.

After the war, Soo fell out with the management at Stoke, frustrated at being played out of position, and in September 1945 was transferred to Leicester City, (then managed by the same Tom Mather, who originally signed him for Stoke) for a reported £5,000. In July 1946, he moved on, again, to Luton Town, where he made a further 78 appearances, scoring 5 goals for The Hatters.

Soo ended his playing career at Chelmsford City. However, he continued to be involved in football, spending the next 25 years as a Manager and Coach, largely in Italy (in Serie A with Padova), and across Scandinavia. Soo was the coach of the Norway side at the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki. He also managed Scunthorpe United in 1959/60. As a manager and coach he was considered to be a disciplinarian and a hard taskmaster and gained a reputation amongst clubs as someone who was difficult to work with.

After retiring from football, Soo remained in Sweden. On a visit back to the UK in 1975 he said, ”I have two good jobs in Sweden, which involve a lot of walking” (he worked in a hotel and for the British Consulate in Malmo). Soo returned to the UK in the early 1980’s and settled in the Shelton area of Stoke on Trent. Sadly, he developed Alzheimer’s disease in later life and died in a hospital in Cheadle, Staffordshire in January 1991.

There is no doubt that Frank Soo was a skillful footballer and he was a pioneer. That his story is not more widely known may be down to the war interupting his football career, to him spending many years abroad, or to him simply being reluctant to talk about his own past.

The Frank Soo Foundation was created in Soo’s honour in 2016, the aim of which is to promote his story, continue his legacy and encourage more people from East and South East Asian (ESEA) backgrounds to participate in football. The Foundation continues to campaign for the Wartime England matches to be regrded as “official” internationals and for an honorary England cap to be awarded to Frank. In my opinion, at the very least, the FA should recognise the so-called, “Victory” matches as full internationals.

Frank Soo has recently been honoured with induction into the National Football Museum Hall of Fame, celebrating his achievements on the pitch and his role as a pioneer for being England’s first-ever player of Asian descent.

Frank’s younger brother, Ronnie, was signed by Cables in December 1937, in the face of competition from several other clubs, who obviously believed that the footballing talent ran in the family. Unfortunately, Ronnie never really fulfilled the footballing promise of his older brother. During the war, Ronnie Soo, like Frank, joined the RAF, but was sadly killed in an air raid over Germany in January 1944.

His youngest brother, Kenneth, signed professionally for Derby County, before moving around non-league circles with Ilkeston Town, Grantham, Sutton Town and Biggleswade Town.